In

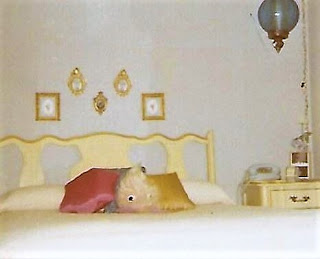

1963, other than a date to the high school dance and a LadyBug shirt dress, what more could a teen girl

want? Not that I recall asking for a Princess phone; my parents, however, gave

me a powder blue one for Christmas, with a rotary dial that did double-duty as a night light.

Without a separate line, of course, my

Princess phone operated as an additional telephone set on one home line. Same phone

number as our home phone, same line as the parents who would pick up the phone

and say “Hang up, now,” that phone hosted multiple viewing parties after it

finally was installed.

Without a separate line, of course, my

Princess phone operated as an additional telephone set on one home line. Same phone

number as our home phone, same line as the parents who would pick up the phone

and say “Hang up, now,” that phone hosted multiple viewing parties after it

finally was installed. Unlike today, however, we had no

call-waiting, no caller ID. We had to be respectful of time limits because the

operator could break in to say, “There’s an emergency call for this number.” We

would be in deep, dark trouble for playing pranks using the phone, like calling

a random number to ask “Is your refrigerator running?” A simple thumb and

forefinger could press a lever to release the plug from the jack and the phone

could disappear as quickly as it appeared.

Unlike today, however, we had no

call-waiting, no caller ID. We had to be respectful of time limits because the

operator could break in to say, “There’s an emergency call for this number.” We

would be in deep, dark trouble for playing pranks using the phone, like calling

a random number to ask “Is your refrigerator running?” A simple thumb and

forefinger could press a lever to release the plug from the jack and the phone

could disappear as quickly as it appeared.

The only question my brother asked

as I left for college: “Can I have your phone?” He did not care that it was a

pretty, blue Princess. I did; I declined his request.

I loved that Princess phone and I

used it until I married, leaving my parents’ home for my own.